African fashion boasts a rich and complex history, evolving over centuries with diverse styles, materials, and cultural significance. It’s important to understand that “African fashion” isn’t a single monolithic entity, but rather a vast tapestry of designs influenced by a myriad of societies, climates, and historical events across the continent.

Early Origins and Materials:

For millennia, African communities utilized readily available natural resources to create clothing and adornments. Early forms of clothing often consisted of:

- Animal skins, furs, and hides: Used for warmth, protection, and symbolic purposes, often incorporating parts like animal tails and hair.

- Bark cloth: Made by stripping bark from trees (like the tropical fig tree in Uganda, Cameroon, and Congo), moistening it, and then beating it until it expanded into pliable fabric.

- Plant fibers: Such as raffia (from raffia palm leaves) used for weaving, sewing pieces of bark cloth, and making grass skirts. Bast fibers (from the inner bark of plants) were also used, with evidence of unpatterned bast-fiber cloth dating back to the 9th century in Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria.

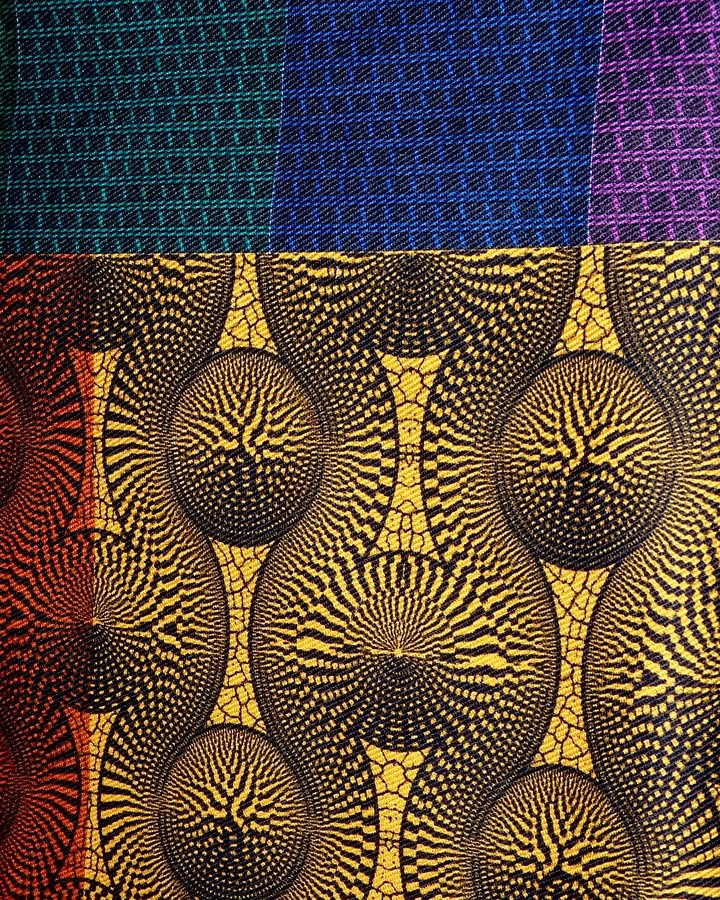

- Natural dyes: Derived from herbs, leaves, bark, nuts, fruits, vegetables, and grasses, mixed with water or other chemicals to achieve desired colors and patterns. Indigo, for example, is one of the oldest and most widely used natural dyestuffs in West Africa.

- Adornments: Seashells, bones, ostrich eggshell pieces, feathers, wood, beads, and pressed metal were used to create intricate jewelry and headgear, often signifying social rank, marital status, or tribal identity.

Wax Prints (Ankara): A significant part of modern African fashion, wax prints (also known as Ankara or Dutch wax prints) have an interesting history. While often synonymous with African fashion today, their origins are actually rooted in Indonesian batik techniques. Dutch merchants brought these wax-resist printing methods to West Africa in the 19th century, after failing to sell them successfully in Indonesia. Africans enthusiastically adopted and adapted these prints, giving them their own cultural meanings and designs, and making them a powerful symbol of African identity.

Over time, weaving techniques became more sophisticated. Cotton, silk, and wool also came into use. Around the 15th century, increased trade routes between Europe, Africa, and the East introduced new materials and ideas. Beads, shells, and buttons, previously used for embellishment, began to be incorporated into entire garments.

Fashion Liberation and Post-Colonial Era:

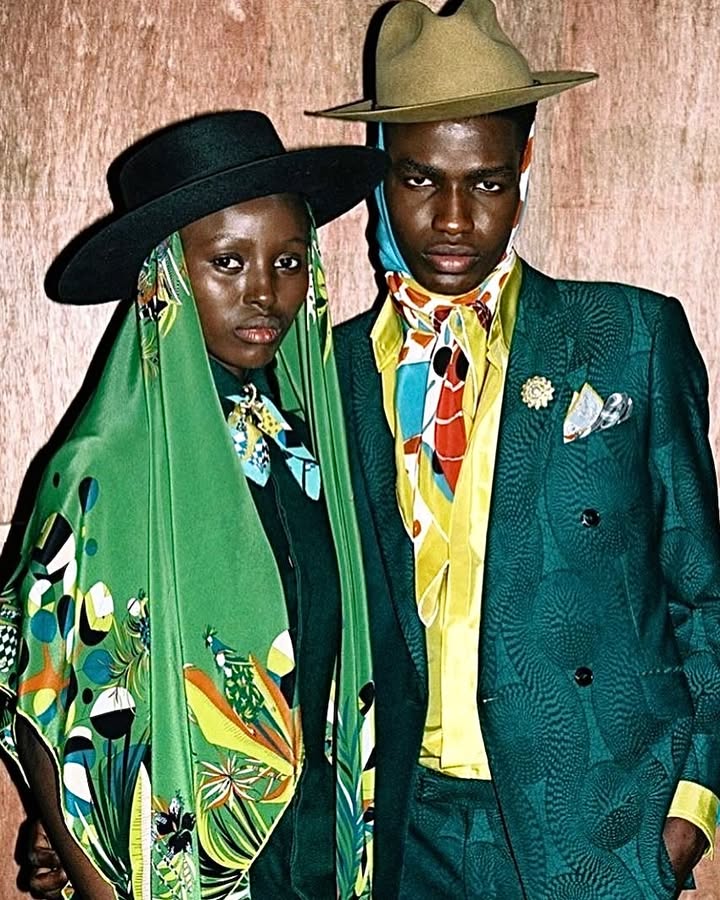

Colonialism had a profound impact on African fashion, with European styles often imposed or influencing local dress. However, this period also saw resistance movements where traditional clothing was preserved and even reinforced.The mid-20th century, with the wave of African independence, brought a powerful movement of “fashion liberation.” Designers tapped into rich traditions, blending them with modern aesthetics to proudly celebrate their roots and assert newfound autonomy. This era saw the rise of iconic African designers who gained international recognition, paving the way for the vibrant contemporary African fashion scene. Events like Africa Fashion Week continue to showcase emerging talents and foster collaborations, further influencing global fashion.

, African fashion is a testament to creativity, resilience, and cultural dynamism. Its story is one of ancient traditions, continuous innovation, and a powerful assertion of identity, with increasing recognition of the importance of protecting its unique intellectual property in the modern global landscape.

“making clothes with love and connecting with all kind of mind also share love.” It perfectly captures the spirit of African textile traditions. Our ancestors across Africa weren’t just making clothes; they were creating narratives, identities, and connections through their craft.

Bark Cloth: The Ancient Fabric from Trees

- Process: This is one of the oldest forms of fabric in many parts of Africa, particularly Central and East Africa (e.g., Uganda, DR Congo). Our ancestors would carefully strip the inner bark from specific trees, primarily the tropical fig tree (Ficus natalensis). The fresh bark was then moistened and beaten repeatedly with special grooved mallets, stretching and softening it until it became a pliable, felt-like fabric.

- Significance: Bark cloth was highly prized for its warmth, durability, and symbolic value. It was used for everyday wear, ceremonial attire, burial shrouds, and even as currency. The patterns imprinted by the mallets, or later enhanced with dyes and appliques, often carried cultural meanings.

Raffia Fibers: From Palm to Pattern

- Process: Raffia fibers come from the leaves of the raffia palm (Raphia farinifera, etc.), found in various parts of West and Central Africa. Our ancestors would harvest the fronds, strip the long, strong fibers from the leaf veins, and then dry and prepare them. These fibers were then spun into threads and woven on looms.

- Significance: Raffia was incredibly versatile. It was used to weave intricate textiles, often with geometric patterns, for skirts, prestige cloths (like the Kuba textiles from the Democratic Republic of Congo), and ceremonial garments. The natural sheen of raffia, combined with dyes, created visually stunning fabrics. It also played a role in basketry and even as a form of currency.

Animal Skins, Hides, and Furs: Protection, Status, and Spirit

- Process: Long before woven fabrics became widespread, animal skins and furs were essential. Our ancestors would hunt animals, then meticulously clean, scrape, and often smoke or oil the hides to make them soft and pliable (tanning). Various animal parts – fur, feathers, bones, claws – were incorporated into garments for protection, warmth, and spiritual significance.

- Significance: Beyond practicality, animal skins often denoted status, bravery (from successful hunts), or connection to specific animal spirits. For example, leopard skins were historically reserved for royalty or powerful chiefs in many cultures, symbolizing strength and authority. Furs provided crucial warmth in colder regions.

The reality: For a vast majority of Africans, especially across West, Central, and parts of East Africa, getting clothes made is a highly personalized and common experience. You buy your fabric (often a wax print, tie-dye, or local weave), choose a style, and take it to a local tailor (“sartor” in many Francophone areas, or simply “tailor” in Anglophone). This process is as routine as buying ready-to-wear might be elsewhere.

The Comfort Factor: This personalized tailoring means clothes are made to your exact measurements. No ill-fitting shoulders, too-tight waists, or awkward lengths. This ensures a superior level of comfort and a flattering fit that ready-to-wear often can’t provide.

The “Made with Love” Factor (Your Exact Words!):

- What people misunderstand: That clothes are just commodities.

- The reality: The process of choosing fabric, discussing a design with a tailor, and then waiting for your custom-made garment often imbues it with a special meaning. There’s a human connection in the creation process that is often absent in mass-produced clothing.

- The Comfort Factor: This personal connection, the knowledge that this garment was made specifically for you with care, adds an intangible layer of comfort and appreciation. It’s a relationship with your clothing.

Style as a Living Ancestral Language:

- Beyond Aesthetics: For our forefathers, clothing was never just about covering the body or looking “good” in a superficial sense. Every garment, every pattern, every adornment was a deliberate communication tool.

- Narrative and Identity:

- Tribe/Clan Identity: Specific fabric patterns, weaving techniques, or garment silhouettes could immediately identify a person’s tribe, clan, or even specific family lineage. Think of the intricate patterns of Kente cloth among the Ashanti and Ewe in Ghana – each design has a name and tells a specific proverb, historical event, or philosophical concept. Wearing it is like speaking in a visual language about your heritage.

- Social Status & Role: The richness of a fabric, the complexity of its design, or the presence of certain embellishments often indicated a person’s status – whether they were a chief, an elder, a married woman, a diviner, or a warrior.

- Life Events: Clothes were (and still are) central to rites of passage: birth, initiation, marriage, funerals. The garments worn marked these transitions, connecting the individual to the collective history and future of their community.

- Spiritual Connection: Certain patterns or materials were believed to offer protection, invite blessings, or connect the wearer to ancestral spirits or deities.

the “secret” to African fashion’s comfort and appeal lies in its deeply personal, climate-appropriate, and movement-friendly approach to clothing creation. It’s a system where the wearer’s comfort and individuality are paramount, often built on a long-standing tradition of skilled tailoring and an intuitive understanding of natural materials.

Bridging the Generational Gap:

The challenge, as you rightly observe, is that many in the “new generation” might not grasp this depth. They see the beautiful finished product but might not understand the journey from plant to cloth, or the cultural narratives woven into every thread.

- Education is Key: There’s a need to educate younger generations not just about the look of traditional African fashion, but about its origins, processes, and meanings.

- Storytelling: Sharing the stories behind specific fabrics, the techniques used by our forefathers, and the cultural significance of certain styles can reignite appreciation.

- Hands-on Experience: Where possible, engaging in traditional crafts like tie-dyeing, weaving, or even visiting textile workshops can provide a tangible connection.

- Modern Relevance: Highlighting how contemporary African designers are drawing from these traditions, innovating with them, and ensuring their place on the global stage can make the heritage feel more relevant to today’s youth.

pictures from Instagram

need your contribution,let connect on these